In my first post I talked about how tracking “narratives” in online news and conversation was among my motives for taking this deep dive into the literature on public epistemology. Establishing a set of clear definitions for narrative and related terms is an important goal toward this end. Such definitions must be both usable and explanatory. In aggregate, they must be comprehensive enough to establish full coverage of the problem space: misinformation and narrative pathologies, writ large. To get a sense of what might constitute a framework in this sense, we can take a look at some that already exist.

Two frameworks that come up often in even a cursory review of literature about narrative are those of Joseph Campbell and Kenneth Burke: the Hero’s Journey and the Dramatistic Pentad, respectively. Both are extremely widely known, especially as writing tools. While they are ultimately based upon academic work done by the two critics, these systems have a life of their own, passed along in simplified formulations and reformulations that are abundant online. In this post I will talk about the frameworks more-or-less as popularly understood, saving a deeper dive into the works of Campbell and Burke for a later series of posts.

Kenneth Burke: The Dramatistic Pentad

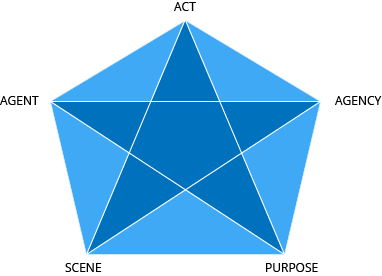

Kenneth Burke’s pentad offers a simple framework for understanding dramatic action, which he breaks down into five component terms: agent, act, scene, purpose and agency. These terms are straightforward enough in their commonplace definitions and we can spell them out as who, what, when/where, why and how, respectively.

Act, Scene, Agent, Agency, Purpose. Although, over the centuries, men have shown great enterprise and inventiveness in pondering matter of human motivation, one can simplify the subject by this pentad1 of key terms, which are understandable almost at a glance. (Grammar,2 p xv)

Indeed, knowledge that drama should include these elements is at least as old as Aristotle’s Poetics. For Burke, their familiarity is a virtue which underwrites the utility of the system.

By examining them quizzically, we can range far; yet the terms are always there for us to reclaim, in their everyday simplicity, their almost miraculous easiness, thus enabling us constantly to begin afresh. When they might become difficult, when we can hardly see them, through having stared at them too intensely, we can of a sudden relax, to look at them as we always have, lightly, glancingly. And having reassured ourselves, we can start out again, once more daring to let them look strange and difficult for a time. (Grammar, p xvi)

Burke’s pentad is a reminder that a dramatic work must balance these elements in such way that is not—to borrow from Aristotle— improbable (or impossible). To do this, we must emphasize the terms not in isolation, but in their interactions.

This presentation taken from an online course in rhetoric3 is typical4.

The fully-connected pentagonal framing encourages us to analyze each of the edges independently5 so we can better understand the mutual influence of the terms in pairs. These comparisons—which Burke calls ratios—can then inform aspects of the plot and allow viewers and critics to make sense of the dramatic action. But, more than this, we can wallow in the comparisons to take in all the ambiguities that they imply, exaggerated by their placement in a context of action.

We take it for granted that, insofar as men cannot themselves create the universe, there must remain something essentially enigmatic about the problem of motives, and that this underlying enigma will manifest itself in inevitable ambiguities and inconsistencies among the terms for motives. Accordingly, what we want is not terms that avoid ambiguity, but terms that clearly reveal the strategic spots at which ambiguities necessarily arise. (Grammar, p xviii, emphasis in original)

We do not want to solve these ambiguities, but rather to mine them for insight.

Hence, instead of considering it our task to "dispose of" any ambiguity by merely disclosing the fact that it is an ambiguity, we rather consider it our task to study and clarify the resources of ambiguity. (Grammar, p xix)

By naming each of the ratios we add a simple mechanism for making reference to these comparisons. In analyzing the X-Y ratio, we consider the ways in which the term Y is motivated by the term X. Taking a trivial example, a simple maxim for the scene-agent ratio is that “a character must fit her setting.” Slightly more elaborate applications of this ratio might explain the excess of lobbyists in Washington, why there are no atheists in foxholes or why Willie Sutton robbed banks.

Insofar as men’s actions are to be understood in terms of the circumstances in which they are acting, their behavior would full under the heading of a “scene-act ratio.” But insofar as their acts reveal their different characters, their behavior would fall under the heading of an “agent-act ratio.” (The International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences)

The concept of ratio is generic—comprising a total of twenty6 for the full pentad—but, for Burke, the term Act is number one among equals. The above-mentioned Nature of Writing lesson on the pentad7 summarizes the act-motivating ratios by asking us to consider the topic of “students skipping class” and working through the relevant ratios one at a time.

Agent-Act: The act is the result of the agent’s motivation. The students were lazy. That’s why they skipped classes on a regular basis.

Agency-Act: The act is the result of the available tools or means. Since no buses ran that early, the students couldn’t make use of public transport to get to class. That’s why many skipped class on a regular basis.

Scene-Act: The act is the result of the setting and circumstances. The school is right beside a beach. Can you blame young people for being drawn away to admire the local scenery?

Purpose-Act: The act is the result of a particular purpose. The students skipped class because skipping class is fun.

Act-Act: The act is the result of another act. In the first class, the teacher embarrassed one of the students, so the students felt entitled to skip class.

Much more subtle and/or elaborate analyses of motive are obviously possible. A sophisticated use of ratios in messaging is quite often all that people mean by framing. In this passage from a pedagogical blog post on Burke8, we can see how an analysis of ratios might be put to use in writing a persuasive piece on the subject of “graffiti” (an act).

In this example, some people in the community argue that the young people have no respect for the property of others, so they commit this vandalism. Burke would call that an agent→act ratio. Bad people commit bad acts. The solution to the problem, defined by this combination, might be to punish or re-educate the agents. However, others argue that the bad neighborhood creates bad people who do this. That would be a scene→agent ratio (We could actually think of this as a three term combination, scene→agent→act.) Here the solution might be to improve the neighborhood through addressing root causes, such as poverty or homelessness. On the other hand, perhaps young people see all of the graffiti in the neighborhood and want to imitate the behavior. That would be a scene→act ratio which might imply a graffiti removal campaign to clean up the city. Finally, someone else might argue that the graffiti is legitimate political or artistic expression. That would be a purpose→act ratio. In that case, the solution might be to engage with the community and address the issues that the perpetrators are talking about. Each of these ratios defines the problem in a different way and implies a different kind of solution. Each implies different kinds of arguments. It is not clear that any one of these perspectives is “correct,” but they are all possible positions. The pentad has opened up a lot of possibilities for discussing the situation.

The applications of this framework are numerous, covering the full gamut from writing and world-building to analysis and critical studies. But some assembly is required, as the mileage will vary with the literacy of the analyst. We’ll take a closer look at A Grammar of Motives in a later post to see that in more detail.

Joseph Campbell: The Hero’s Journey

Joseph Campbell’s work on mythology was originally intended to highlight the features common to myths, and to lay the groundwork for deeper theories of mythology. The Hero’s Journey is a writing framework based on his most famous work, The Hero with a Thousand Faces. George Lucas credits Hero as inspiration for his Star Wars Trilogy and Joseph Campbell is particularly well known because he was subsequently featured in a Bill Moyers documentary filmed at Lucas' ranch. Millions saw the documentary and perhaps a comparable number are familiar with the story-writing template.

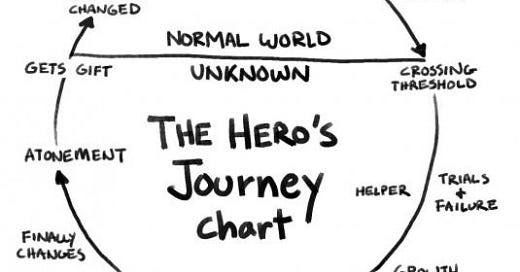

In its most common presentation, the Hero’s Journey is depicted as a cycle with a number of stages on its circuit. This depiction taken from a 2017 blog post9 is not unusual.

A common version of the framework—popularized by screenwriter Christopher Vogler in his 1992 book The Writer’s Journey—defines a cycle with twelve stages.

The Ordinary World. We meet our hero.

Call to Adventure. Will they meet the challenge?

Refusal of the Call. They resist the adventure.

Meeting the Mentor. A teacher arrives.

Crossing the First Threshold. The hero leaves their comfort zone.

Tests, Allies, Enemies. Making friends and facing roadblocks.

Approach to the Inmost Cave. Getting closer to our goal.

Ordeal. The hero’s biggest test yet!

Reward (Seizing the Sword). Light at the end of the tunnel

The Road Back. We aren’t safe yet.

Resurrection. The final hurdle is reached.

Return with the Elixir. The hero heads home, triumphant.

This popular version is itself a reduction and re-arrangement of the seventeen chapters that Campbell presented in The Hero with a Thousand Faces, summarized here by an online writing aid.

Call to Adventure (Separation): The hero receives an invitation to go on a quest.

Refusal of the Call (Separation): At first, the hero hesitates to accept the invitation, either because the journey is too dangerous, or because they have other obligations at home.

Supernatural Aid (Separation): Someone the hero looks up to inspires them to accept the call to adventure, or gives them tools that will help them on their quest.

Crossing the Threshold (Separation): The hero begins their quest and leaves the ordinary world and their everyday life.

Belly of the Whale (Initiation): The hero encounters the first real danger in their quest, and wonders whether or not to turn back—but ultimately pushes forward.

Road of Trials (Initiation): The hero undergoes several trials and learns from their mistakes.

Meeting With the Goddess (Initiation): The hero meets a mentor figure or ally, who offers help or advice.

Woman as Temptress (Initiation): The hero encounters temptations that threaten to steer them away from their heroic journey, which they must nobly avoid.

Atonement with the Father (Initiation): The hero undergoes a personal metamorphosis by confronting an aspect of their own character that has been preventing them from achieving success, such as their own fear, greed, or self-doubt.

Apotheosis (Initiation): The hero transforms into a better person, and goes forward with new insight and clarity on what they must do to win.

Ultimate Boon (Initiation): The hero achieves victory in their quest.

Refusal of Return (Return): At first, the hero is reluctant to go back to the familiar world after their exciting journey and transformation.

Magic Flight (Return): Even though the hero has achieved victory on their quest, they still face dangers as they try to return home.

Rescue from Without (Return): An outside ally or mentor helps guide the hero safely home.

Crossing the Return Threshold (Return): The hero returns to the familiar world, and tries to adjust to their old life.

Master of Two Worlds (Return): The hero finds a balance between their home life and the person they become on their quest.

Freedom to Live (Return): The hero gets used to their normal life and lives peacefully. Call to Adventure: The hero receives an invitation to go on a quest.

A recent book10 on screenwriting proposed a Hero's Journey with a total of 195 stages. As a writing template, this level of detail can be extremely useful. But, even in Hero, the seventeen chapters merely add detail to a much simpler analytical model presented by Campbell, his monomyth. Only three stages are presented in Campbell’s monomyth: separation, initiation and return.11

This simpler model is flexible and potentially quite useful in the analysis of narrative generally. In a certain sense, the monomyth defines the smallest unit of content that we might call a myth.12 We should be able to adapt this approach to use with narrative more generally. We will look more closely both at the three stages of the monomyth and the more fully-elaborated seventeen steps of Campbell’s “Hero’s Journey” in a future series when we do deep dive into The Hero with a Thousand Faces.

Putting the two systems to use

Both of these systems are used primarily as writing aids. But the ratios in Burke’s pentad and the three stages of Campbell’s monomyth can also be taken as simple models in the analysis of action and narrative. Indeed, in both cases, this is much closer to the usage the author intended.

In a written response13 following the widespread adoption of the pentad by English departments for pedagogy in writing, Burke notes:

In the Rhetoric for instance, Aristotle’s list is telling the writer what to say, but the pentad in effect is telling the writer what to ask.

[ …. ]

Maybe I can now make clear my particular relation to the dramatistic pentad, involving a process not quite the same as either Aristotle’s or Irmscher’s. My job was not to help the writer decide what he might say to produce a text. It was to help a critic perceive what was going on in a text that was already written. (p332)

Burke’s interest in form is highly congruent with the stated objectives of this newsletter and echoes some of its core findings so far.

A work has form insofar as one part of it leads a reader to anticipate another part, to be gratified by the sequence. (p331)

In his 1945 book A Grammar of Motives, Kenneth Burke did not set out to devise a framework for effective writing technique, his interest was critical—i.e. dialectical and metaphysical. As a cover term, he chose dramatistic.

I called these notions "Dramatistic" because they viewed language primarily as a mode of action rather than as a mode of knowledge, though the two emphases are by no means mutually exclusive. (p330)

A dramatistic framework puts emphasis on human motives by centering its analysis on action but only offers synoptic glimpses of the larger whole.

The titular word for our own method is "dramatism," since it invites one to consider the matter of motives in a perspective that, being developed from the analysis of drama, treats language and thought primarily as modes of action. The method is synoptic, though not in the historical sense. A purely historical survey would require no less than a universal history of human culture; for every judgment, exhortation, or admonition, every view of natural or supernatural reality, every intention or expectation involves assumptions about motive, or cause. Our work must be synoptic in a different sense: in the sense that it offers a system of placement, and should enable us, by the systematic manipulation of the terms, to "generate," or "anticipate" the various classes of motivational theory. And a treatment in these terms, we hope to show, reduces the subject synoptically while still permitting us to appreciate its scope and complexity. (Grammar, pp xxii-xxiii)

It is not difficult to imagine a wide range of applications for the pentad in the analysis of text. And Burke is not bashful about walking us through the options. But how much does it help us with the problem of tracking and analyzing public text on news issues? Looking for content about terms and ratios certainly seems like a slightly more concrete framing of the tracking problem—and one which is potentially much more solvable. But Burke would be quick to acknowledge that the nature of these terms changes from one “circumference” to the next. We appear to have traded one difficult problem for another. Nevertheless, finding agents and scenes in text are more tractable problems than finding narratives. In this sense, the pentad’s terms and ratios amount to a substantive starting point.

Similarly, Hero’s Journeys do not offer a complete model for our domain, but do have a number of promising ingredients. The forms and structures laid out in the Hero’s Journey are exemplars of the sorts of roles and scripts that play an important role the conception of anticipation articulated by Mead and offer a mythical counter-point to the archetypes of Jung. With respect to the latter, the temptress, goddess and helper should all be familiar figures.

Owing just to their widespread adoption as templates for writing fiction, we should expect to see examples from these systems all over popular media. Even if we are skeptical about the universal nature of the forms themselves, their common usage has undoubtedly had an impact on the expectations of large audiences.

Viewing the situation from a wider perspective, the monomyth could serve as a starting point for modeling an atomic narrative: the smallest unit of content that we could still call a narrative. This could have interesting definitional implications, but I will save a deeper dive into the monomyth for a later post.

Neither of these frameworks comprises a full set of answers to our questions, but it seems clear that fragments of both will inform our ultimate conclusions. One such conclusion may be that the investigation of narrative is qualitative, not quantitative; more art than science.

It is not our purpose to import dialectical and metaphysical concerns into a subject that might otherwise be free of them. On the contrary, we hope to make clear the ways in which dialectical and metaphysical issues necessarily figure in the subject of motivation. Our speculations, as we interpret them, should show that the subject of motivation is a philosophic one, not ultimately to be solved in terms of empirical science. (Grammar, p xxiii)

Interestingly, this is one of only ten usages of “pentad” in a Grammar of Motives. None of the usages are treated as a proper name, rather as references to the five terms and their ratios. Grammar is better understood as the bounds of casuistry than as a model in the formal sense.

Burke, Kenneth. A Grammar of Motives. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1969.

Instead of a pentagram, Burke used the metaphor of a hand and its fingers, which is perhaps better from the perspective of depicting parts operating in a unified whole, but substantially less elegant in its presentation of ratios:

We have also likened the terms to the fingers, which in their extremities are distinct from one another, but merge in the palm of the hand. If you would go from one finger to another without a leap, you need but trace the tendon down into the palm of the hand, and then trace a new course along another tendon.” (Grammar, p xxii)

That said, the hand metaphor is perhaps more deeply suggestive of Burke’s overall process than the simplicity of the pentagram allows for. Even so, Burke switches metaphors to get at that idea:

And so with our five terms: certain formal interrelationships prevail among these terms, by reason of their role as attributes of a common ground or substance. Their participation in a common ground makes for transformability. At every point where the field covered by any one of these terms overlaps upon the field covered by any other, there is an alchemic opportunity, whereby we can put one philosophy or doctrine of motivation into the alembic, make the appropriate passes, and take out another. From the central moltenness, where all the elements are fused into one togetherness, there are thrown forth, in separate crusts, such distinctions as hose between freedom and necessity, activity and passiveness, cooperation and competition, cause and effect, mechanism and teleology. (Grammar, p xix)

i.e. as pairs of terms

Ratios are not symmetric (“X-Y” and “Y-X” are independent ratios) and reflexive pairs (“X-X”) are not allowed. 5 times 5 is 25 minus 5 is 20.

John R. Edlund, November 8, 2018. “Using Kenneth Burke’s Pentad“ Teaching Text Rhetorically

Neal Soloponte (2017), The Ultimate Hero’s Journey.

Campbell, Joseph. 2012. The Hero with a Thousand Faces. 3rd ed. The Collected Works of Joseph Campbell. Novato, CA: New World Library. p23

Of course this is just the form of one kind of myth: a hero myth. One of the biggest complaints about the widespread adoption of Hero’s Journey templates is that they privilege only one kind of story. Worse, it is a story template that centers a stereotypically masculine protagonist (hero) whose journey is buffeted throughout by often sexist tropes.

Kenneth Burke. 1978. “Questions and Answers about the Pentad” in College Composition and Communication, Vol. 29, No. 4 (Dec., 1978), pp. 330-335