Extending our Knowledge with Language and Thought

In Part 1, we explored the role that experience plays as the foundation of knowledge. But we could certainly say that we “know” far more than we’ve witnessed with our own senses. But how much more? And how do we come by that knowledge?

Reason

As we build upon the justified beliefs we have acquired through perception, remembering and reflecting, we apply reason to extend our knowledge. Here a full survey of epistemology could get bogged down in distinguishing concepts like self-evident, analytic, a priori, prima facie, essential, necessary, and indefeasible. While I will not avoid defining these terms where we need them, they are not as important as some other meta-principles in the space of reasoning.

First, the scope of concepts and the definition of words are often important in validating inferences in one or more of these ways. All vixens are female is true by virtue of the meaning of vixen and female. More generally, “encountering a sentence which expresses a truth does not enable one to consider that truth unless one understands the sentence.” (p107) Understanding a word or concept is a thorny problem that we will review in more detail when we discuss philosophy of language in a subsequent posts. Suffice it to say here, interpretation often involves a complex interplay between better understanding a word/concept on the one hand and better understanding the intended signal (qua truth value, or propositional content, or whatever) on the other. “For all that these points establish, our understanding of word meanings (including sentence meanings) is simply a route to our grasping of concepts and shows what it does about the truths of reason only because of that fact.“ (p133)1

Second, grounding and uninterrupted causal chains once again play a crucial role in distinguishing the justified from the unjustified.

Finally, we must follow Kant in broadly distinguishing the empirical from the analytic, in the sense that the former is knowable only through confirmatory experience. In doing so, we allow for non-empirical knowledge, but we become more committed to the implicit boundary between internally-justified and externally-justified beliefs.

Knowledge of propositions a priori in the broad or ultimate provability sense, unlike knowledge of those a priori in the narrow sense, depends on knowledge of some self-evident proposition as a ground. But neither kind depends on knowledge of any empirical proposition, and in that sense both kinds are “independent of experience.” (p113)

Testimony

So far the picture is extremely personal. An epistemology is the product of perception and reflection, mental processes experienced by individual embodied human beings. This is important, as it reflects the myriad nature inherent in a more aggregated concept of epistemology—a public epistemology. Yet it falls short on a related, but distinct collective notion: that which we colloquially refer to as knowledge, specifically: all that we know as a civilization, whether it is merely written or otherwise documented or it is actually known by someone in the manner defined above.

Surely if no one knew anything in a non-testimonial mode, no one would know anything on the basis of testimony either. More specifically, testimony-based knowledge seems ultimately to depend on knowledge grounded in one of the other sources we have considered: perception, memory, consciousness and reason. (p160)

For both public epistemology and for knowledge (in its broad sense), we must depend on the testimony of others.

A major epistemological point that the case of testimony shows here is that a basic belief—roughly, one basic in the order of one’s beliefs, and so not premise-dependent—need not come from a basic source of belief: roughly one basic in the order of cognitive source and so not source-dependent. A belief that is not based on, and in that sense does not depend on, another belief may come from a source of beliefs that does depend on another source of them. (p155)

The most basic act of testimony is attesting: simply saying that such and such is true. Correspondingly, the most cogent aspects of this action to a typical listener would be whether the proposition attested is true and, relatedly, whether the speaker is credible. We cannot trust everyone (perhaps they are mistaken), but trusting no one would severely limit our potential scope of knowledge. “Intellectual virtue—and epistemic responsibility conceived as a kind of virtue—are attained when we achieve a reasonable “mean” between excessive credulity and unwarranted skepticism.“ (p152) But we each must find the appropriate balance between skepticism and credulity.

Skepticism takes the form of filtering (or down-weighting) propositions attested by untrusted sources, sometimes with the help of secondary cues such as apparent sincerity or propositional consistency. Credulity takes the form of accepting the attested proposition, but without all the justificational fixins. But the justificational poverty of testimony amounts to a substantive bootstrapping problem that requires a pragmatic mixture of verification and trust.

Whatever might be possible in principle, it is doubtful that we can always avoid relying on testimony, at least indirectly, in any actual appraisal of testimony. Even one’s sense of an attester’s track record, for instance, often depends on what one believes on the basis of the testimony. Think of how one news source serves as a check for another: in each case, testimony from one source is tentatively assumed and checked against testimony from another. How, then, can we globally justify testimony if we can never rely on it in the process? (p166)

Modeling the process is more akin to modeling poker than it is amenable to economic abstractions like Nash equilibrium. I have to make bets as I go, because the game goes on. But some of those bets are at least partly designed to discover how my “opponent” is playing, which is itself a moving target influenced by my own tactics. That is to say, my poker moves have a mix of various utilities, in addition to purely economic ones: I will pursue some amount of informational utility and even aesthetic utility as I play; and these utilities will often be highly context-dependent and opportunistic, such as when I discover a tell or a particular hand has reached a high-stakes impasse, or an opponent has clearly gone on tilt.

Likewise, language games involve a similar mix of utilities. Each move I make will serve a variety of utilities—semantic, informational, aesthetic, even economic—and these utilities are balanced in a highly context-dependent and opportunistic manner. Audi distinguishes between two types of testimony: propositional and demonstrative; and he associated these with two kinds of learning: propositional and conceptual. This distinction is important as far as it goes. I would argue that this is even better understood as a continuum (instead of as discrete classes) and also as modes of interpretation (instead of as types of testimony). The separation of process and content may not be as clean as some of this taxonomizing suggests.

For misinformation, we commonly and sometimes sternly correct children, whereas we patiently instill habits of correct reporting. This correlational sense that children apparently develop might provide a kind of analogical justification for taking others to be providing, when they give testimony, information they have obtained. (p164)

A listener needs to balance between processing the information a speaker is offering and evaluating their credibility regarding that information. Not only do most speakers stand on a middle ground (for most listeners), but also “trust can be retroactive as well as retrospective.” (p153) With respect to a new conversational partner who has demonstrated consistency with known truths over the course of conversation, Audi paraphrases the process as follows.

What happens is apparently this. As her narrative progresses, the constraints set by my independent beliefs relax, and, regarding each statement she makes, I form beliefs not only non-inferentially, but also even spontaneously, in the sense that any constraints that might have operated do not do so. Her statements no longer have to be tested by under [sic] the gaze of my critical scrutiny, nor are they filtered out by the more nearly automatic checking the mind routinely does when people offer information. (p153)

In the end, the credibility of testimony is heuristically reduced to sincerity and competence. In other words, do they appear honest (or do they tend to be honest) and are they competent to provide the information in question: either via direct experience or accumulated expertise. And the credibility of the testimony is a major factor in its justification. But our own beliefs will play a role as well. “Receptivity to testimony-based justification sometimes requires already having some measure or justification: for believing the attester credible or for believing p, or for both.” (p158)

Inference

With the addition of testimony, we have a much larger pool of (possibly) justified beliefs from which to build more complex epistemological objects via the application of reason. Given some beliefs that are in some way or another justified (more on this later in this post), we can use inference to extend our inventory of beliefs. Taking a classic example, the fact that we hold the justified beliefs that Socrates is a man and that All men are mortal justifies our conclusion that Soctates is mortal. With a few exceptions (e.g. object beliefs) the building blocks of belief (and knowledge and reason) are taken to be propositions. Propositions can be analyzed in terms of their predicates (is mortal, is a man), their arguments (men, socrates), and their quantifiers (all).

What I conclude—the conclusion I draw—I in some sense derive from something else I believe. The concluding and the beliefs are mental. But neither what I conclude, nor what I believe from which I conclude it, is mental: these things are contents of my beliefs, as they might be of yours. They are not properties of anyone’s mind, as in some sense the beliefs themselves are. Such contents of belief—also called objects of belief—are commonly thought to be propositions (or statements, hypotheses, or something else that can be considered to be true or to be false but is apparently itself not a mental entity). (p177)

Thus we distinguish between the inferential process (a mental undertaking) and the inferential content (an abstraction). Additionally we distinguish between episodic inferences and structural inferences: the former involves concluding that a window is open on the basis of a breeze; the latter is the more traditionally presented type of inference seen in the Socrates example. Both are important to properly understanding epistemology, but note that failures in episodic inferences play a major (and under-appreciated) role in the misinformation context. Giving “the impression” that a proposition is true is often just as effective as asserting it.

Deductive Reasoning: Given a set of discrete premises that includes both A and If A then B (ϕ), we can conclude B, as long as A and ϕ are both valid.

Subsumptive Reasoning: A subclass of deductive reasoning based on the inclusion of a specific example (Socrates) in a class with universal character (all men).

The universal structure (all men) available in our example is rare, but the architecture of reason supports a number of forms of inference weaker than deductive reasoning that can themselves provide grounds for justified true beliefs given a felicitous application.

Inductive Reasoning: Given a set of exemplars showing a property with no counter-examples, we can tentatively conclude the property applies to all remaining exemplars. The potential threat of future counterexamples makes the conclusion defeasible. (e.g. The sun will rise tomorrow.)

Abductive Reasoning: Given a set of premises that offer “the most likely explanation” for a conclusion, we can often draw that conclusion. (e.g. The window is open.)

Analogy: Given similarity between two items or situations, we can apply knowledge of the one to the other.

Knowledge, Belief and Justification

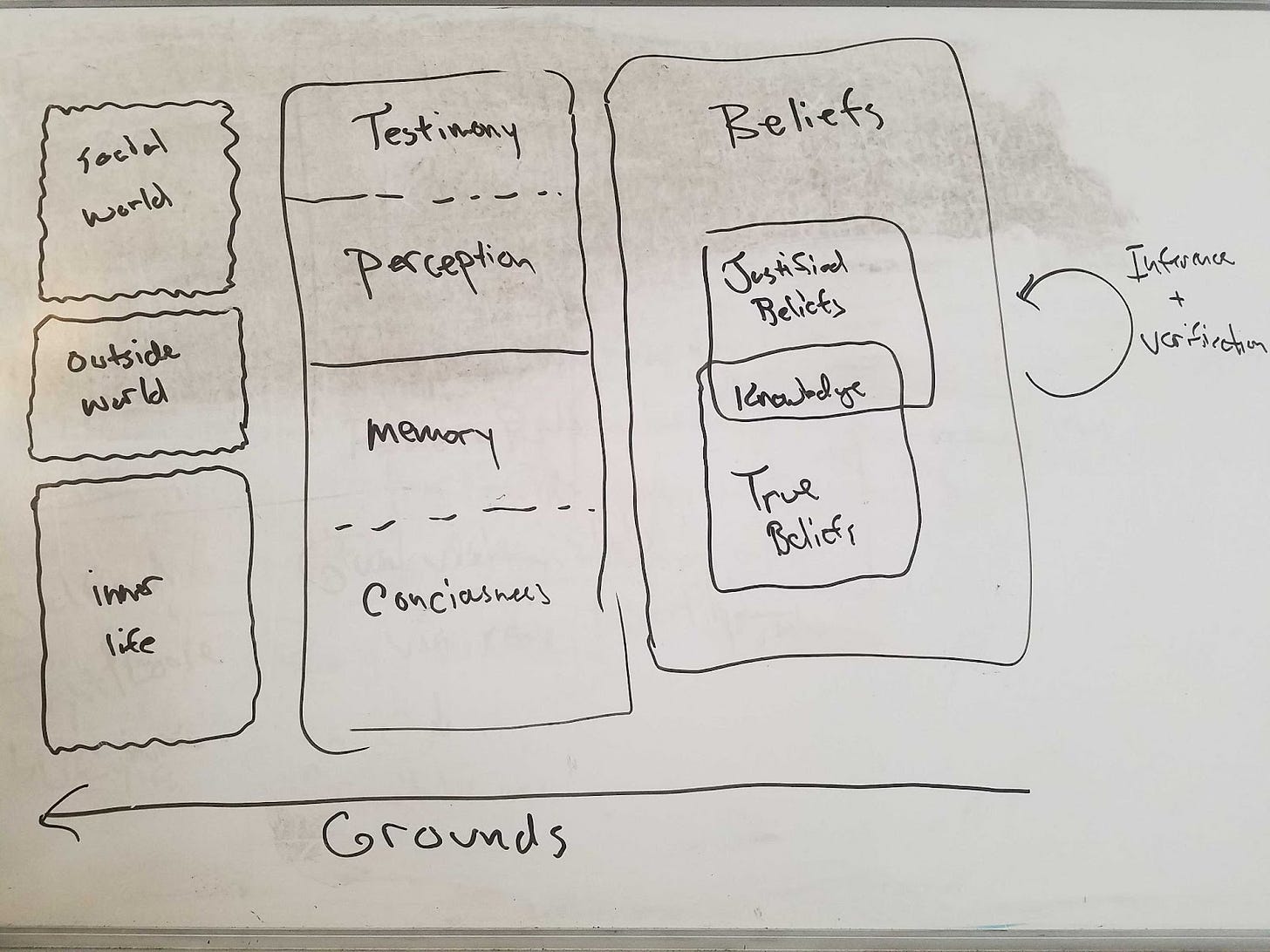

In the basic picture that is emerging, beliefs (which are themselves typically propositions), participate in a doxastic complex structured with various relations of support and grounding, that have been derived through processes of inference and can be undermined (or reinforced) by processes of verification. Among beliefs, we can distinguish those that are justified and those that are true: a pair of overlapping subsets. And within that subset of true justified beliefs, we can find knowledge, in the epistemological sense. “We might say that knowledge is true belief justified in the right way on the right kind of ground.” (p291)

Again, there is a lot to unpack here. First, the space of beliefs is structured in two important ways: via 1) causal chains of inference that are 2) grounded in experience. Second, these relations suggest an epistemic space with numerous justified beliefs but little actual knowledge, since so many of our beliefs are ultimately grounded on testimonial evidence and so are not really grounded at all. But “mere” justified belief is, quite often, good enough.

When such a chain is grounded on knowledge, we can call it an epistemic chain and distinguish four classes of these chains (p211):

Infinite chains have no anchor

Circular chains anchor themselves

Justificatory chains are anchored on beliefs (other than knowledge)

Epistemic chains are anchored on knowledge

The chains in the first class, infinite chains, are hard to even comprehend. They do not constitute knowledge. Circular chains are also unlikely to occur “naturally” given the need for a grounded true premise to kick them off2. In any event, they also would not constitute knowledge. The third class, justificatory chains, are also not knowledge but are justified.

The last class, epistemic chains, are themselves knowledge, and their anchors can be referred to as foundational knowledge. We can take this complex of facts to justify the epistemic regress argument, which dates to Aristotle.

Epistemic Regress Argument: If one has any knowledge, one has some direct knowledge. (p215)

A contrarian take on grounding advocated by coherentists suggests that a fifth type of chain also supports knowledge, because it is psychologically direct.

Coherentist chains are anchored on psychologically direct beliefs

This flexibility allows for concepts like coherence to ground knowledge via backdoor mechanisms internal to the process of chaining and verification. But coherentism is controversial, not least because foundational grounding is the relation that underlies most of the influential theories of epistemology. It is not difficult to imagine a wide variety of coherent sets of propositions that would nevertheless not hold up to a scrupulous verification against the outside world. Worse, we would have no basis for evaluating a belief system or for comparing two fully-consistent belief systems.

The question is especially striking when we realize that two equally coherent systems, even in the same person at different times, could differ not just on one point but on every point: each belief in one system might be opposed by an incompatible belief in the other. (p223)

That said, coherence is an important mechanism for evaluating justification, just not the only one.

This defeating role of incoherence is important., but it shows only that our justification is defeasible—liable to being outweighed (overridden) or undermined—should sufficiently serious incoherence arise. It does not show that justification is produced by coherence in the first place, any more than a wooden cabin’s being destroyed shows that it was produced by the absence of fire. (p228)

And coherence is not a grounding relation, but a structuring relation.

Whatever coherence between beliefs is, it's an internal relation: whether it holds among beliefs is a matter of how those beliefs (including their propositional content, which is intrinsic to them) are related to one another. (p222)

Moreover, coherence is a relation that is best understood on limited domains. Hence it cannot be understood as a source of knowledge.

Incoherence is absent when there are mutually irrelevant beliefs as well as when there are mutually coherent ones. Mutual irrelevance between two sets of beliefs certainly does not make one of them a justificational or epistemic basis for the other. (p228)

While testimony adds substantial material to be chained by reason, its addition also complicates the situation with respect to grounding these chains.

The effects of increased familiarity show that one person’s indirect belief may be another’s direct belief, just as one person’s conclusion may be another’s premise.

[ ... ]

There is a wide-ranging point illustrated here that is important for epistemology, psychology, and the philosophy of mind: we cannot in general specify propositions (if there are any) which can be believed only inferentially or only non-inferentially—intrinsically basic propositions. (p181)

Recasting non-basic propositions as basic ones in the disaggregated case causes the categories themselves to collapse in the aggregate and beget the postmodern condition of pure relativity (inter-subjectivity). Validating and confirming propositions—especially where those propositions are basic for the evaluator and/or where they ground chains that are important to larger structures of belief—then becomes an important ongoing process. Some amount of this can be done with reason. Looking at inference from the perspective of epistemological effects we can distinguish between inferential extension, which adds to the overall volume of knowledge, and inferential strengthening, which improves the grounds or volume of justification for knowledge already present.

Once justified, the justification and its grounds may be forgotten or mis-remembered, leaving only the conclusion as a justified belief.

Memory can retain beliefs as knowledge, and as justified beliefs, even if it does not retain the grounds of the relevant beliefs. [ ... ] Moreover, when the grounds are not retained and none are added, one might find it at best difficult to indicate how one knows, beyond insisting that, say, one is sure one remembers, perhaps adding that one surely did have grounds in the past. (p198)

Furthermore, we must reject notions of doxastic volunteerism, which suggest that we have conscious control over the beliefs that we entertain, hold justified, etc. As hard as we concentrate on seeing the sailboat in the illusion art, we return to the abstract dot patterns the moment we re-focus our eyes.

Conclusion

Taken together, these observations suggest an externalism about knowledge and internalism about justification. That is to say that we can depend on reflection to sort out beliefs but grounding in the real world is a crucial element of knowledge.

If these internalist views about justification and externalist views about knowledge are roughly correct, then the main point of contrast between knowledge and justification is this. Apart from self-knowledge, whose object is in some sense mental and thus in some way internal, what one knows is known on the basis of one’s meeting conditions that are not (at least not entirely), internally accessible, as states or processes in one’s consciousness are. By contrast, what we justifiably believe, or are simply justified in believing, is determined by mental states and processes to which we have internal (introspective or reflectional) access: our visual experiences, for instance, or our memory impressions, or our reasoning processes, or our beliefs of supporting propositions. All of these are paradigms of the sorts of things about which we can have much introspective knowledge. (p275)

From here the conversation turns on a number of distinctions about what, specifically, constitutes knowledge, justification, value, truth and virtue. These are philosophically interesting questions, but not as relevant here. For our purposes it suffices to say that knowledge is beliefs that are both true (in the sense that they correspond to reality) and also justified (via the kinds of grounding and chaining discussed above). Adjusting for mistaken beliefs involves insight about error in one or both of these dimensions. Conversely, mistaken beliefs can lead to the mistaken filtering of new testimony and/or a mistaken assessment regarding the credibility of the messenger. Both of these tendencies are crucial to understanding the role of new information in reinforcing existing narratives, and vice versa.

In Part 3, we will wrap things up with a closer look at the landscape of skepticism and systems of virtual knowledge, such as science.

Robert Audi (2011). Epistemology: A Contemporary Introduction to the Theory of Knowledge. Third Edition. Routledge. New York and London.

The example that Audi uses for circular chains is plausible, if a little convoluted. Imagine a situation where someone concludes that the wind is blowing based on a belief that the leaves are swaying, which is itself merely an inference (or perhaps a mistaken perception) based on the belief that the wind is blowing. In an epistemic context, these chains are hard to conceptualize. But, of course, circular reasoning is far more common in moral and procedural settings. This anti-drug ad from the early 1990s comes to mind as an example.