Narrative and democracy

Narratives—through their form and structure—play a central role in the crisis of democracy spreading through the West at alarming speed. But as my series on narrative in international relations should make clear, there is no consistent and reusable definition of narrative. Worse, theoretical knowledge of narrative dynamics—often both quite extensive and creatively deployed—is typically applied in a manner that is superficial and post-hoc. The full list of shortfalls in operationalizing the notion of narrative in the context of information disorders is beyond the scope of this post. But some items in particular are notable in their absence:

a robust model of how narratives operate on on agents (individuals and institutions);

a robust model of the role played by narrative in the maintenance of personal and group identity; and

a clear model of narrative dynamics in the context of the newly fragmented 21st Century media ecosystem.

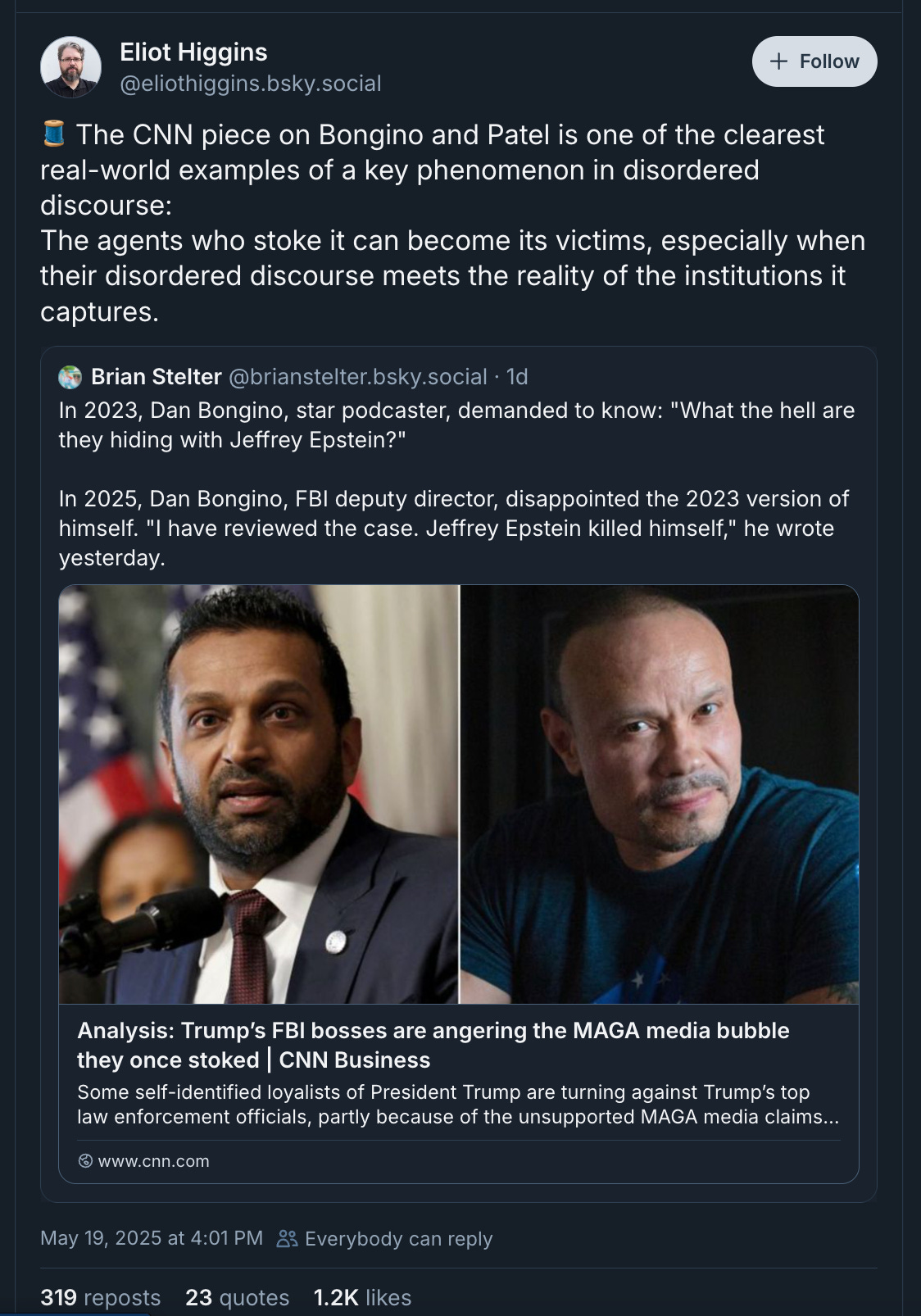

In his keynote lecture at the Cambridge Disinformation Summit last month, Bellingcat1 CEO and Founder, Eliot Higgins, introduced a framework for understanding these dynamics in more detail. He asks the audience to think about the crisis of democracy as a type of discourse disorder—a framing that he has since promoted consistently on social media as explanation for various recent misinformation incidents.

The lecture is worth watching in its entirety. Higgins’ main argument is that disordered discourse has led to captured institutions and regressive democracy; and that the first step in ameliorating the crisis is isolating the structures and incentives that would need to be targeted in defense of a progressive democracy. He offers a nascent framework to this end, elaborated in enough detail to potentially support intervention playbooks that can help improve public discourse and often even undermine emerging disorders “left of boom” (even when there is no “attacker” per se).2

To underwrite the details of his one hour lecture, Higgins has assembled a (15+ hour!) playlist of Philosophize This! lectures by Stephen West. The topics range from Platonic Idealism to post-Structuralism and cover mostly issues of relevance to public deliberation and epistemology. This list itself is well-curated and worth a listen. The first lecture—about Walter Lippmann and John Dewey—is of particular importance to understanding the relationship between discourse and democracy; how that relationship was co-opted by powerful interests in the 20th Century; and how the fragmentation of the 21st Century has produced the regressive (i.e. pro-authoritarian) democracy that we now confront.

Information disorders and disordered discourse

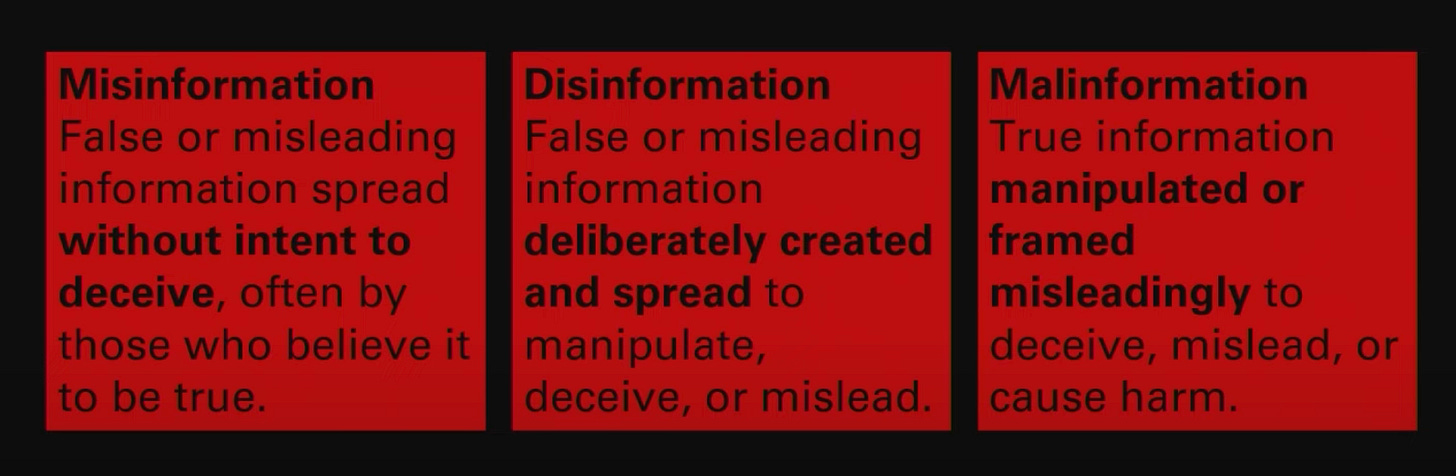

Higgins starts the lecture with an important point that is often misunderstood in ham-fisted discussions of disinformation, Claire Wardle’s three-way partition of information disorders: misinformation, disinformation, and malinformation. These more or less amount to being mistaken, lying and being out-of-context, respectively. (Image: Eliot Higgins, 2025)

Like Higgins, I believe that these distinctions are extremely valuable for a number of reasons.3

Treating all information disorder as disinformation leaves out a substantial portion of the disorder. We should be pursuing interventions for the full spectrum of problems.

Treating misinformation as disinformation hampers corrective efforts—tersely, people do like to be called liars and/or rubes.

But more than this, Higgins suggests that the information frame itself is too passive. Deliberative (Deweyan) democracy requires discourse. “Fact checking websites fail because they create information not discourse.” (Higgins, 2025). Healthy and disordered discourse can then be contrasted on the basis of how we characterize them as processes. Viewed from a distance, these processes can be characterized as progressive (deliberative) and regressive (repressive). Viewed more closely, we can see the following pattern:

Progressive Discourse Regressive Discourse

Verification → Distortion

Deliberation → Division

Accountability → Deflection

Elements of disorder

Higgins arranges the framework around a hierarchy of components.

Elements < Drivers < Agents < Discourse

We have already discussed the elements of disordered discourse. They are from the tripartition of information disorders presented above. The remaining three levels of the hierarchy will be discussed in turn. The structural details of these components each represent opportunities for intervention. A strong implication is that interventions at lower levels are more likely to succeed; that ameliorating drivers is more likely to help than criticizing agents or attacking discourses head-on.

Drivers

Higgins classifies the drivers by type, stressing that various incidences of disordered discourse are driven by different mixes of these elements.

Structural and Technological Drivers

Amplification

Monetization

Decline of Gatekeepers

Media Fragmentation

Psychological and Social Drivers

Cognitive Biases / Motivated Reasoning

Identity and Community

Doctrine Enforcement / Purity

Crisis Catalysts

Fear

Social Fragmentation4

Political and Economic Drivers

Weaponization

Astroturfing

Influence Ops

Policy Failures

Polarization

Political Fragmentation

Drivers are crucial to the story told in this framework. Indeed, interventions are best constructed with the drivers fully in mind. Examples are given at the end of the lecture, but the ultimate remedy appears to be progressive democracy itself. Reversing the pressures that undermine it will be an “all of society” effort.

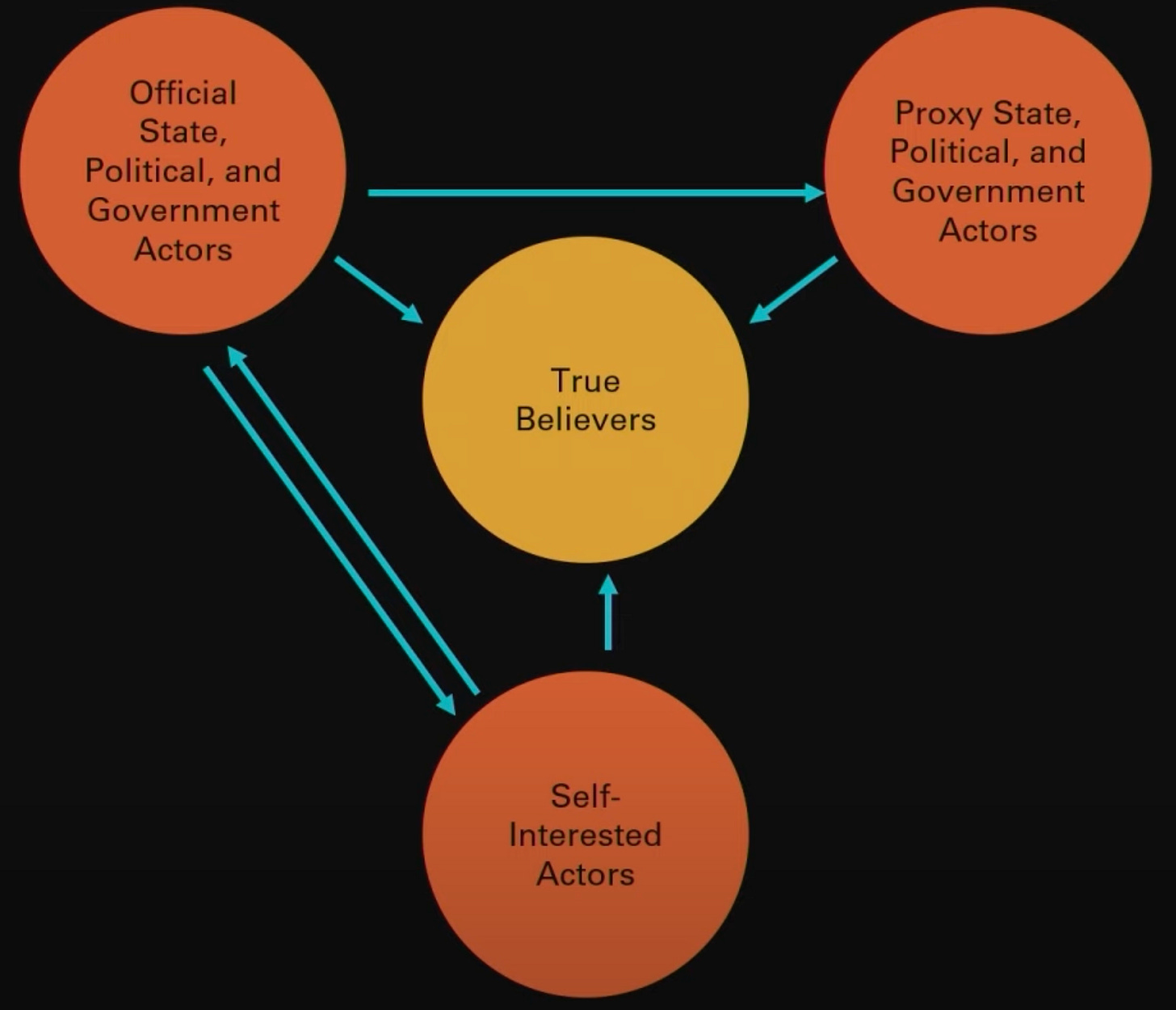

Agents

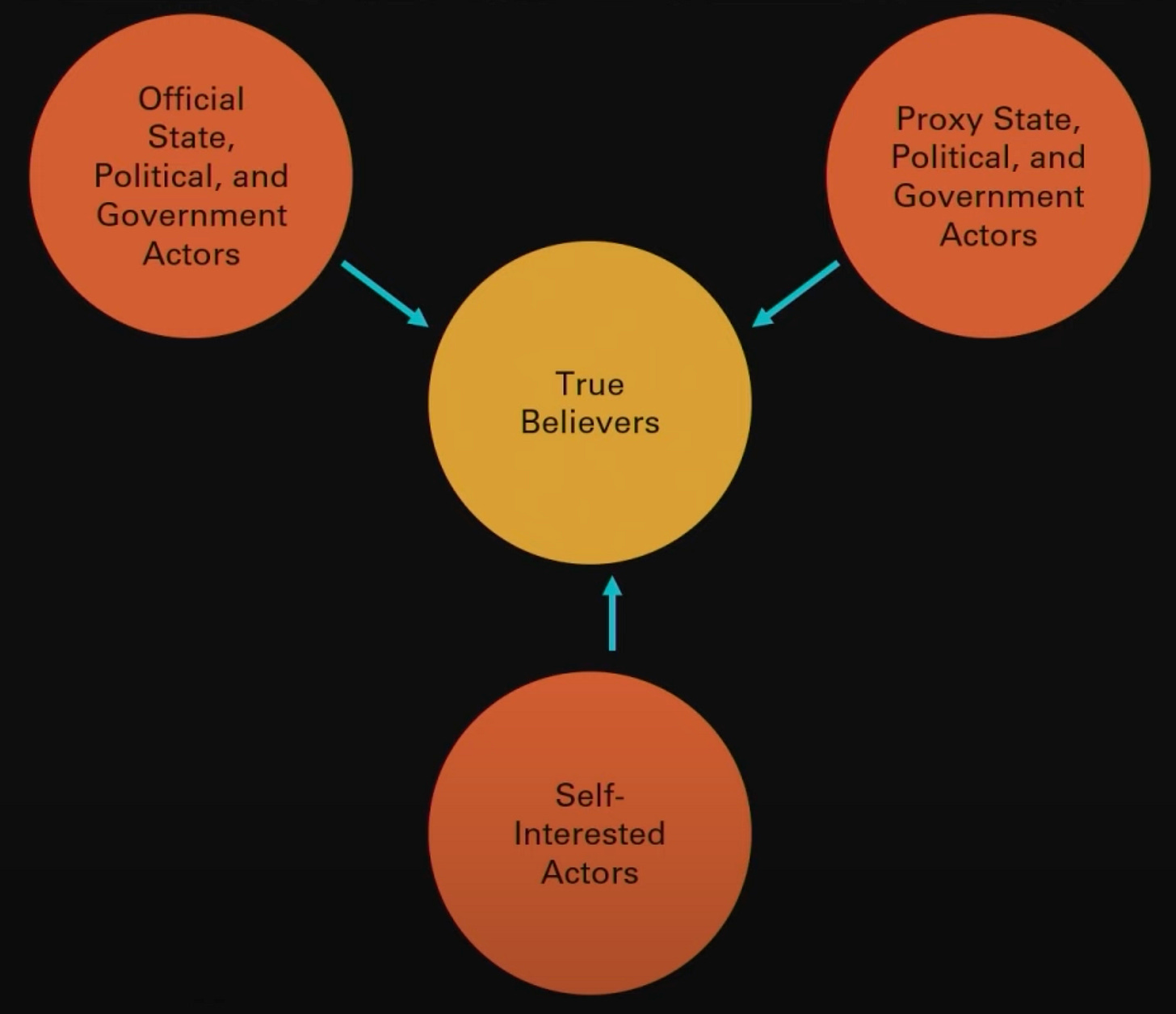

The overall information ecosystem can be modeled as the interactions of four classes of agents (individuals and institutions).

Official State Actors (e.g. the Kremlin)

Proxy State Actors (e.g. RT)

Self-Interested Actors (e.g. Tim Pool)

True Believers (e.g. yer Uncle Bob)

While the (1) vs (2) and (3) vs (4) distinctions may often be difficult to draw in practice, for the framework to be effective we need to do so. The disinformation model often applied—see: Russian interference, etc—distorts the picture to suggest that the information (disorder) flows from (1)-(3) to (4) with the latter as passive victims of malevolent actors. (Image: Eliot Higgins, 2025)

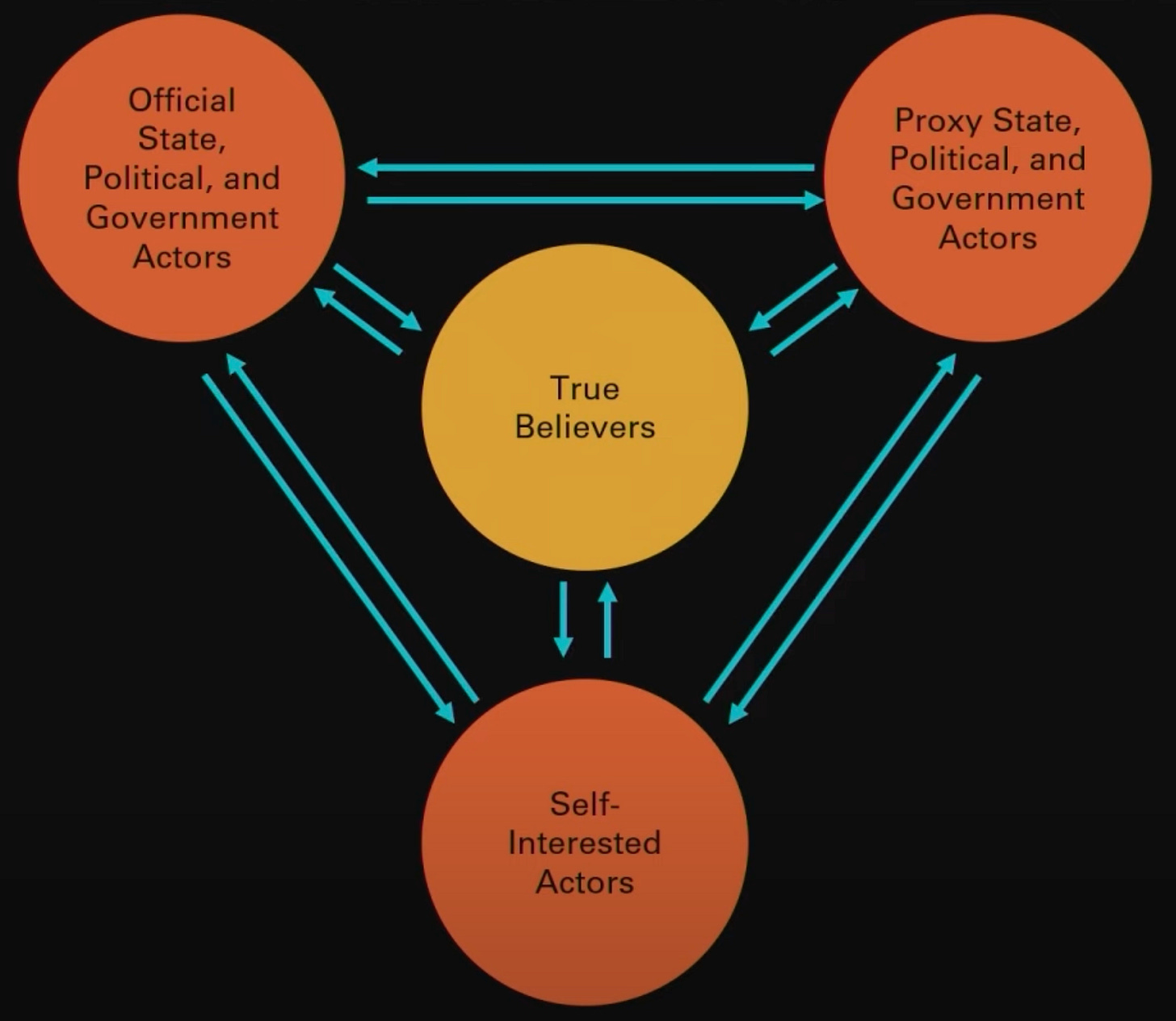

As Benkler et al (2018) suggest in their study of the 2016 elections, the situation is much more dynamic. Indeed, Higgins notes that the disorder flows in all directions. (Image: Eliot Higgins, 2025)

Moreover, specific incidents can be characterized in terms of the flow of these interactions overall. For example, this one describing a collaboration between the Russian U.N. delegation, an American podcaster and Russia Today to influence true believers in the war against Ukraine. (Image: Eliot Higgins, 2025)

Discourse

The level of discourse is where all the action happens, and it is where we can begin to see the importance of narrative to the process overall. To illustrate the dynamics at work here, Higgins walks through a couple of specific vectors of radicalization that can be explained within the framework on offer:

Institutionalized Narratives5

Institutional Capture

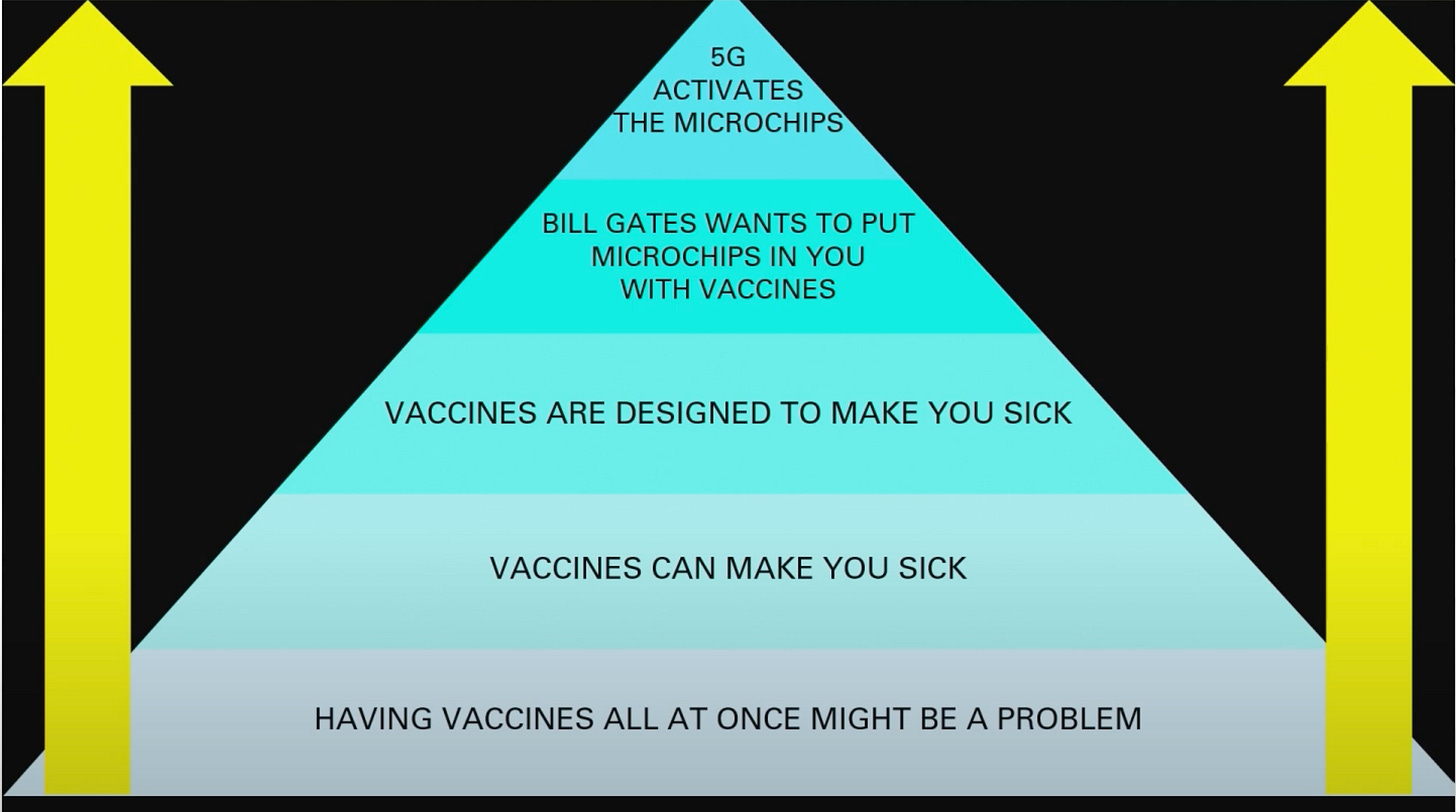

We will look at each of these in turn. But first consider the process of individual capture that can be used to model both. Higgins focuses on the example of conspiracy theories about vaccinations and 5G to emphasize that the process is a ratchet which escalates its victims from “questions” and a vague distrust of authority to kinetic action against 5G towers IRL—a process leveraging the incentives of YouTube algorithms and a community of true believers willing to enforce narrative purity on pains of exile. (Image: Eliot Higgins, 2025)

Note that each step is a “reasonable” escalation of the previous, given the salient open questions and concomitant distrust of conventional authority. Moreover, each step comes with a community of believers willing to protect the narrative from doubt. Backing out is an option, but it comes at the cost of community.

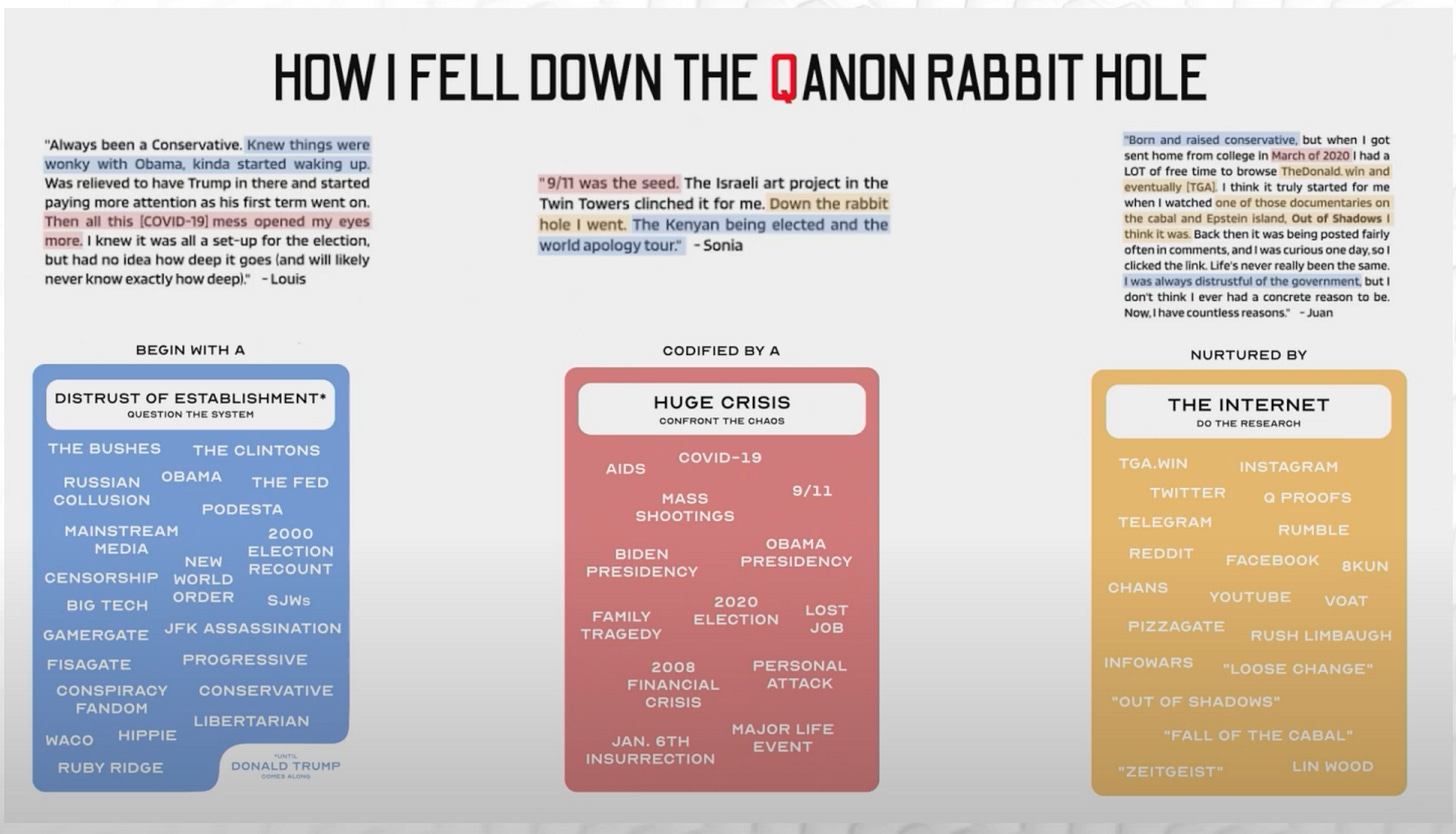

Somewhat directly, as policing and sanctions among adherents become ever more strict and severe, this ratchet-like process gives rise to institutionalized narratives.6 Higgins models the process as a sequence of stages:

Question → Engagement → Identity → Institutionalization → Absolutism

Indeed, QAnon adherents describe the process of radicalization in terms of questions and community as well. (Image: Eliot Higgins, 2025)

The process depends crucially on an establishment unable or untrusted to provide reliable information, especially in a crisis. Failure to build and properly resource institutions up to this task is a major obstacle in ameliorating the present crisis.

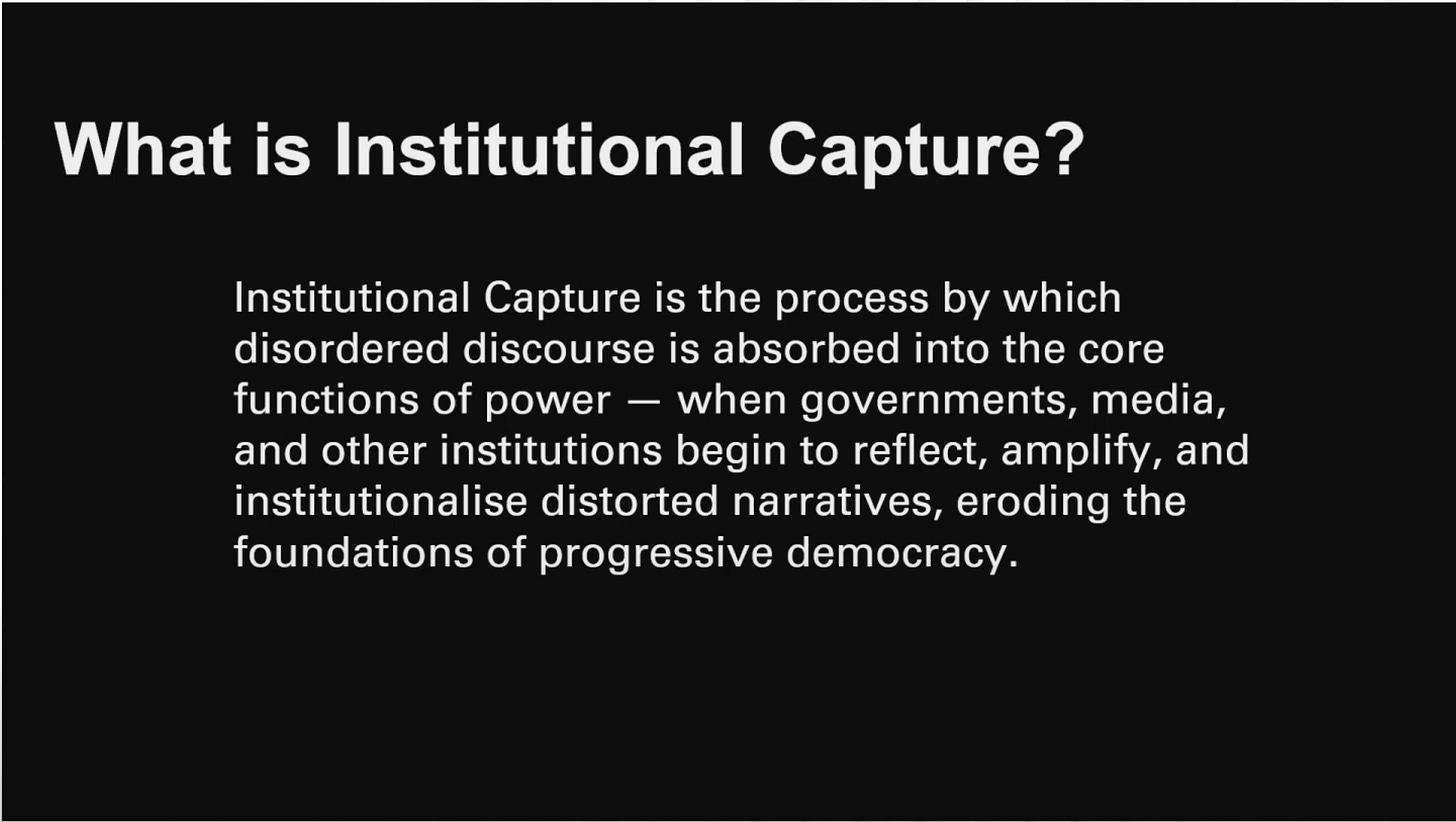

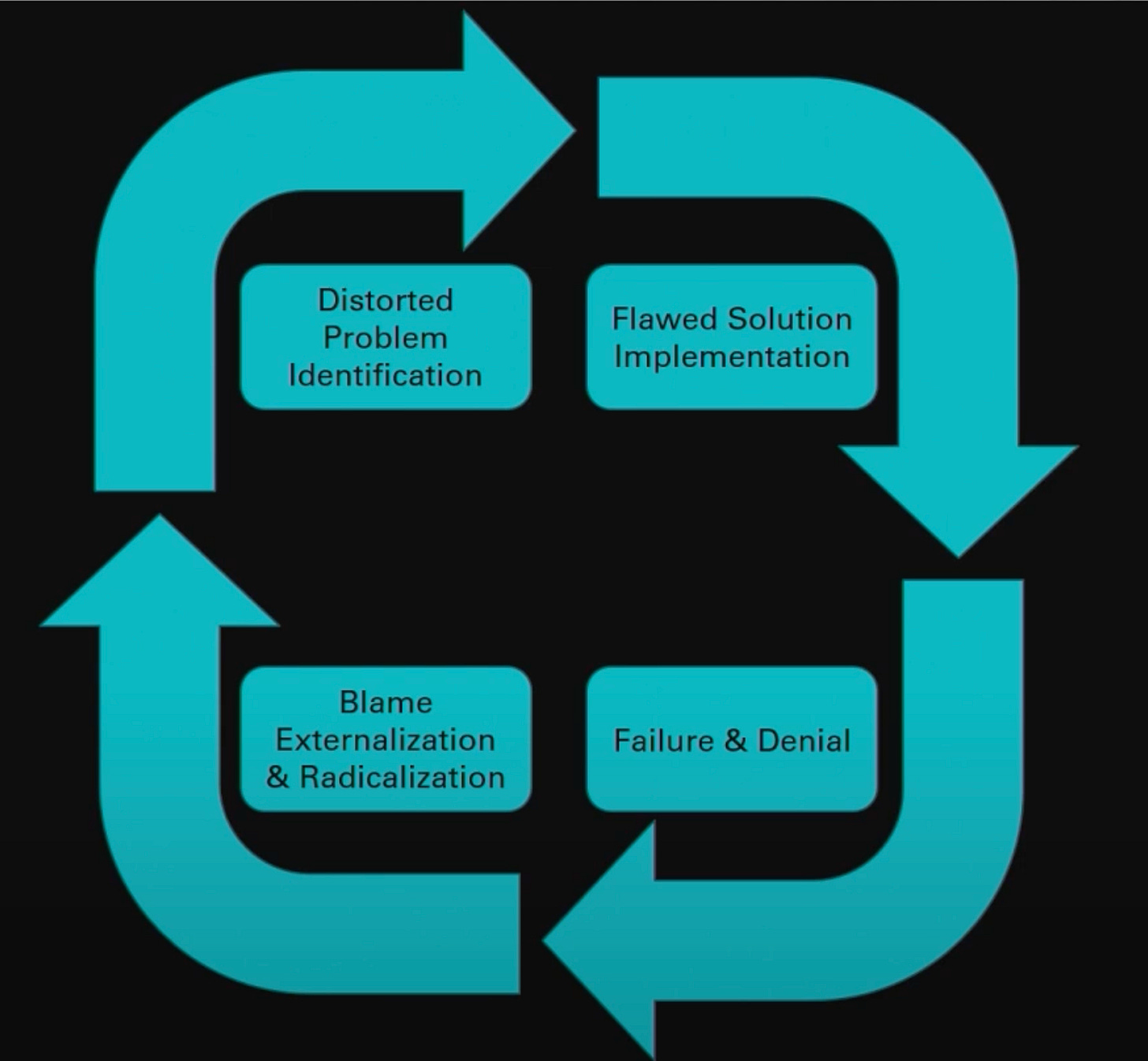

The emergence of these institutionalized narratives is already bad enough. But Higgins’ framework also properly characterizes another ongoing problem in the media ecosystem: institutional capture. In this process, (institutionalized?) narratives are coopted by existing institutions only to colonize the very driving principles of the institutions themselves. (Image: Eliot Higgins, 2025)

Also a ratchet system, institutional capture can be characterized with the following process of integration, expressed as a sequence of stages:

Exposure → Incentive Alignment → Narrative Integration → Behavioral Capture → Structural Embedding

As with the other sequences in this framework, interventions are best targeted at stages to the left. Not being exposed at all is ideal, but ameliorating the potential for incentive alignments could also be a good form of early intervention. Later in the chain, processes of reinforcement make interventions much more challenging—adherents are dug in and censure mechanisms fully operative.

Beyond just run-of-the-mill reinforcement of the kind that converts narrative integration into behavioral capture. we also have the explicit enforcement mechanism characterized in structural embedding. (Image: Eliot Higgins, 2025)

The refusal to admit error drives this feedback loop with substantial assistance from enforced sanctions on group membership.

This is an impressive talk and scholars of information disorders should take it seriously as a guide to future research.

Postscript: Identifying narrative in discourse

Although interventions are best targeted at earlier processes (ameliorating drivers or exposing networks of bad actors), if we want to fully understand the mechanics of the process, especially at later steps, a better handle on what is meant by “narrative” is crucial. Higgins’ framework gives us a good idea how narratives fit into the overall picture; and how central their acceptance and enforcement are to the discourse disorders confronted by democracies in the 21st Century. Even so, we still do not have a clear idea what narratives are in this context: how they are structured and how to find them in the wild, especially before they become fully institutionalized.

Consider the concrete examples regarding vaccines and 5G. Each item on the escalatory hierarchy of narratives takes the form of a single proposition expressed by a relatively simple sentence. But much detail remains underspecified. The narratives that these sentences pick out are anything but simple. Each is really a constellation of of details—actors, plans, motives and activities—that support and elaborate the central claim expressed by the stand-in proposition in the pyramid. In most cases, it is these details that support the inferences and entailments that make the narratives impactful. But these details are often also contested, especially at lower levels of the pyramid, where adoption is more casual and enforcement more lax. These lower-level narratives can be extremely heterogenous with respect to their detailed summarization. A reliable program for identifying and tracking them—especially at early stages of development—is currently beyond our grasp.

The structural details are the source of a narrative’s power: its hold on the collective identity of a given community. Without a better empirical understanding of these mechanics, we cannot elaborate the details at the right edge of the model. And without those details we have no hope of designing interventions appropriate to the level of discourse itself.

Bellingcat is the premier open source intelligence network. You should give them some money. Or at least try some of their puzzles.

See, for example, Walker et al, 2019 and DISARM.

When we were working on AM!TT (now DISARM) at Credibility Coalition in 2019, I was already concerned about this coverage gap—implicit in the kill-chain approach—which takes the problem to be primarily the fault of bad actors (i.e. adversaries) and their operations.

I added this one but fragmentation is the main storyline and the symmetry is appealing.

My term, Higgins’ concept